MOFormer - A Review

Published:

I did not do any research on this topic on my own, but only literature review, there is no content directly from me but only summary. If not directly cited the information is either considered common knowledge or from my references at the end, our main source that is reviewed is [1].

How can we find Metal-Organic-Frameworks with the desired properties using Transformers ?

MOFs are highly tunable materials that can exhibit specific properties when interacting with gases. This versatility makes them valuable in various application fields (as discussed later). This provides us with a multiplicity of potential materials from which we have to select the ones that fullfill our needs the best. Due to the vast number of possible combinations, beyond the reach of conventional material science research, there is a need for scalable synthesis methods that offer researchers a preselected set of material combinations tailored to desired properties.

Material science is a interdisciplinary field that primarily draws on physics and chemistry (our work will be located in the quantum chemistry section of material sciences). Its objective is to analyze, describe and syntetizise materials.

Why we need new Methods to find specialized MOFs right now?

MOFs find significant applications in gas separation and storage, this makes it a good material for air-/pollution filters, drug delivery, water harvesting, hydrogen Storage, CO2-cleansing, and various other uses. For example MOF elements be incorporated to conventional active coal filters in order to filter more effectively targeted certain pollutants depending on the factory type and pollutant output. Also MOFs became a contender for the more recently intensified search for alternative fuel carriers, as the can store a large amount of hydrogen at subatmospheric pressure levels.

These properties primarily arise from the micro-porous nature of MOFs, as they are build as periodic networks of metal units and organic connectors. These structures exhibit high regularity with a lot of pores in them. A good analogy given by experts is the one of an “atomic sponge”, where we have to tune the “atomic stickiness” specified in order to achieve the wanted result. It is essential to consider various factors beyond the physical size of the pores, such as for instance charge distribution and variations in the fields resulting from different interactions.

We will later see that MOFs are build like legos that only have to be assembled with out of the box parts, for this we have a whole catalog of building units that we can combine hierarchically and tune very precise. This simplifies the problem from finding a stable configuration to predicting whether a stable configuration provides the properties we want. The synthesis workflow we propose to optimize includes initially extracting potential MOFs from academic databases or constructing a large number of custom frameworks using a building unit catalog. These MOFs are then filtered through high-throughput analysis, retaining only the top-scoring candidates for further experimentation. The selected MOFs are generated and iteratively modified to achieve the best possible material for the desired requirements.

What actually are MOFs?

Metal-Organic-Frameworks consist of two key components, as the name suggests, one component is a metal-ion also referred to as node. This metal-node serves as a vertex in our cyclic net and the different nodes are connected with organic linkers, also referred to as lignands. These building blocks are commonly known as secondary building units (SBUs). Additionally, SBUs can incorporate some more complex compontents from MOF structures (this is due to the possibility of structuring MOFs hierachically).

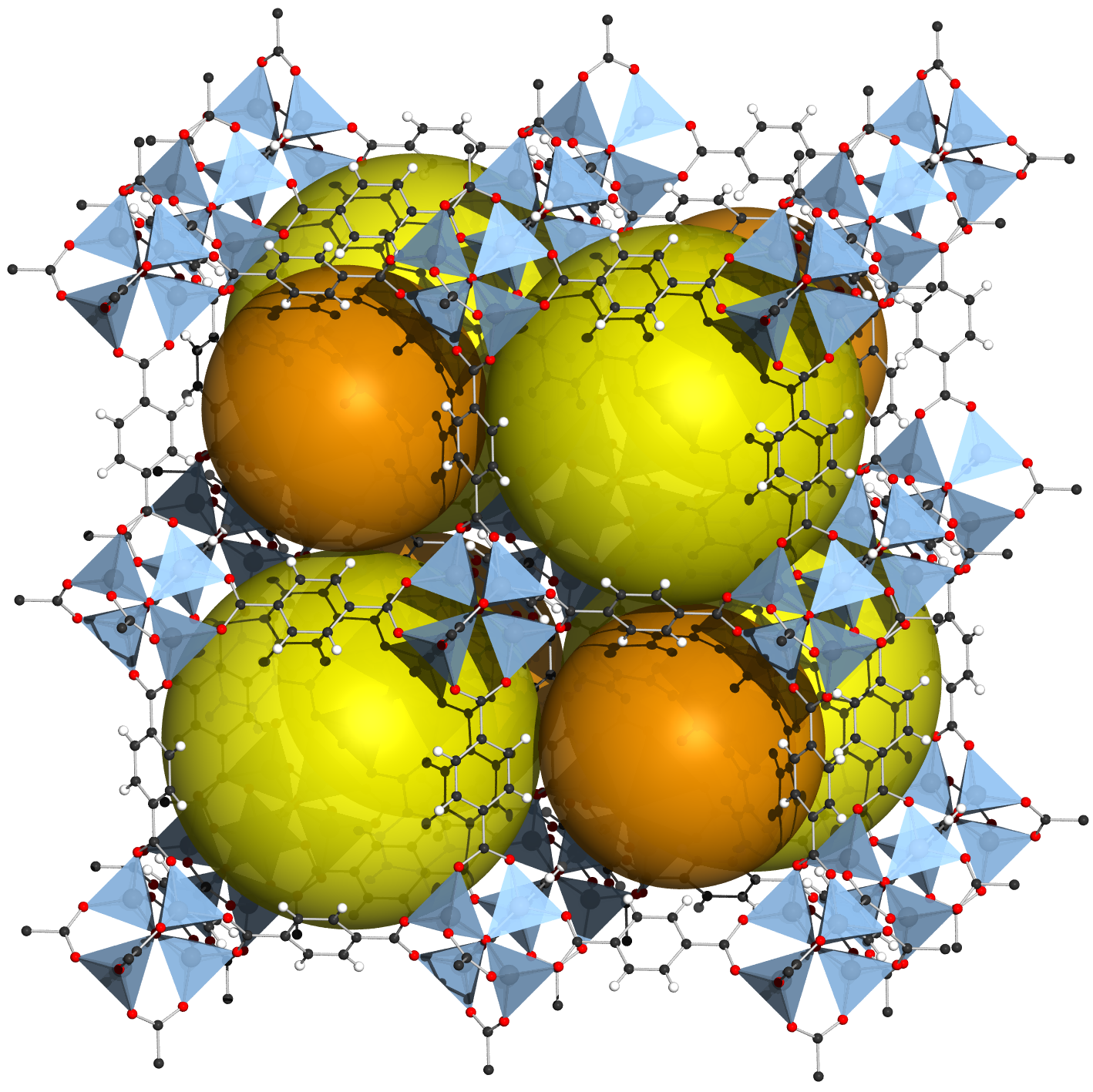

Figure 1: Periodic elements from MOF5, pores are illustrated by spheres (via wikipedia from Tony Boehle)

From this description, we understand the components used to construct a basic MOF. However, it’s important to note that the same materials can have different variants due to variations in geometry and topology. Depending on their method of synthesis and possible environments, the geometry (i.e. how the links and nodes are placed in the space relative to each other) may change, so a MOF can change the geometry for instance if it stores a certain material. When the only difference is in the geometry, we typically consider MOFs to be the same as long as the topology remains homomorphic. The detection and removal of duplicates still pose challenges in practice, but from a machine learning perspective, we do not view it as a problem we need to address.

How is discovery done right now?

The structured synthesis of new MOFs with specific properties is also referred to as discovery. Chemists have developed various methods to facilitate this process, including:

- Chemist knowledge This process just involoves an expert that has gathered some experience in this field using intuition and knowledge what the effects of SBUs are or could be to test them in a structured manner. This is not State of the Art right now, but can achieve good results in some cases.

- Mass testing This approach involves physically creating and testing various MOFs to evaluate their desired properties. However, it is not scalable and can be time-consuming, making it feasible for only a limited set of materials.

- High throughput computational screening This method utilizes simulations and approximations to predict the properties of different materials, such as density functional theory computations, which allows to approximate the properties using a quantum chemical model that simplifies the schrödinger’s equations. These simulatons use the Kohn-Sham-Equations with an initial guess and optimize to achieve a stable structure that can then be used to simulate molecules reacting with materials. Machine learning-based approximations also fall under this category, but they generally offer faster, less accurate results compared to simulations.

- Postsynthetic modification If a MOF already exhibits promising properties, we can selectively modify ligands, nodes, introduce impurities, or combine different structures to refine its performance. However, this approach requires extensive research on the properties and materials involved beforehand.

We will work mostly in the diagram of Reticular Chemistry, which means we have certain rough templates that we can just insert secondary building units and look how feasible this is. (This is a very simplified explanation, but it is enough for understanding our mode of discovery right here.)

A practical synthesis can be done under different conditions, this depends on the components, the MOF, and the expected Material. Common synthesis methods include solvothermal and non-solvothermal techniques (based on temperature), microwave-assisted synthesis, electrochemical methods, mechanochemical approaches, and sonochemical synthesis. This also effects geometry in practice and sometimes it also might effect topology, we generally only try to compute optimized MOF structures (which is implicitly given by our datasets, that also consist of optimized structures).

How are MOFs represented in chemistry and what data is there?

The representation of MOFs varies across different databases, depending on the methods used to obtain the MOFs and their intended applications.

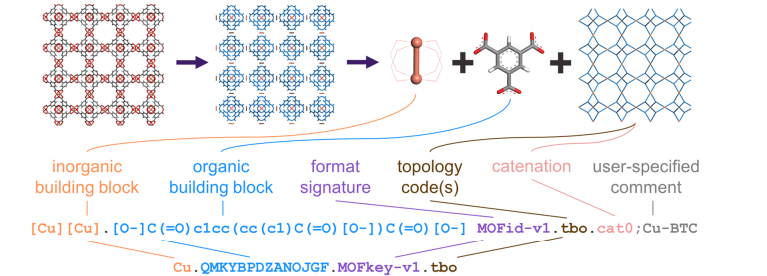

There are mainly to systems that are proven to be exact descriptors of the materials, Systre and Topos Pro, both developed by mathematicians include complicated geometry constructions to achieve a unique representation. These systems are not well-suited for machine learning since they lack direct interpretability and are often to abstract to achieve good results in practice. Also there is the representation in 3D Coordinate systems, here we have given topology as well as geometry, we also call this a full description. Topology in the context of chemical material representations means a graph of the bonds between an atom, while geometry describes how the atoms are sorted in the space in a given material. The 3D representation can lead to a better runtime of DFT Simulations as we have a good intital guess. This leads to a representation as topology graphs, up until now these graphs provide the best descriptions for machine learning (see later). Lastly a less concise representation is given by textual descriptors, these should improve searchability and give some information to researchers, as such they aim to improve interpretability. The presentation used to train our transformers will be MOF-IDs. Derived from the SIMLES descriptor, MOF-IDs are a textual descriptor of MOFs that provide information about the different secondary building blocks (mostly lignants and nodes, but could also include different MOFs in hierarchical combinations), as well a basic information of the net topology (though it should be noted that this presentation is considered topology-agnostic, as the information only gives hints on the type of topology). One example of how the MOF-ID is created is given in Figure-1. This figure also uses the less intuitive MOF-Key which is just a collapsed form of the MOF-ID, that is used for searching and database administration (e.g. duplicate detection).

What is it actually that we are trying to predict?

We want a network that is ideal for finetuning towards the prediction of certain material properties. These properties include for example CO2, Methane or H2 adsorption rates in atmospheric pressure, or more specific attributes such as storage for a specifc drug that now can be delivered straight in a non gasenous form. These properties are often so specific that each model has to be adjusted (at least in the regression head) for each use, therefore it is essential to provide a most versatile model that includes a lot of different material parameters in the latent representation that has to be finetuned.

What can we do with machine learning

As previously mentioned, density functional theory (DFT) simulations provide the most accurate data, making it the benchmark for comparison (considered the gold standard, despite its inherent limitations). Consequently our approach only offers a more computationally efficient method, this means in contrast to (sub-)atomic simulations we are able to test a lot more MOFs for different properties and still be efficient, vertical scalability (this means our MOFs can be a lot more complex and we can enforce even complex hierarchical structures and a lot more smaller variations), and interpretability to help researchers find better MOFs contenders, that can be further analyzed in practice. In summary we can help the chemical researchers in an explorative setting, to find good contenders for future work in a very specialized area.

State-of-the-Arts right now

State-of-the-art algorithms differ in terms of sophistication and specific requirements. A naive approach involves using conventional machine learning algorithms like support vector machines, decision trees, or other model-driven techniques, which can only capture superficial relationships among pre-existing frameworks. Here generally only material property descriptors, containing some properties such as pore size, band width, adsorption or seperation rates, are used.

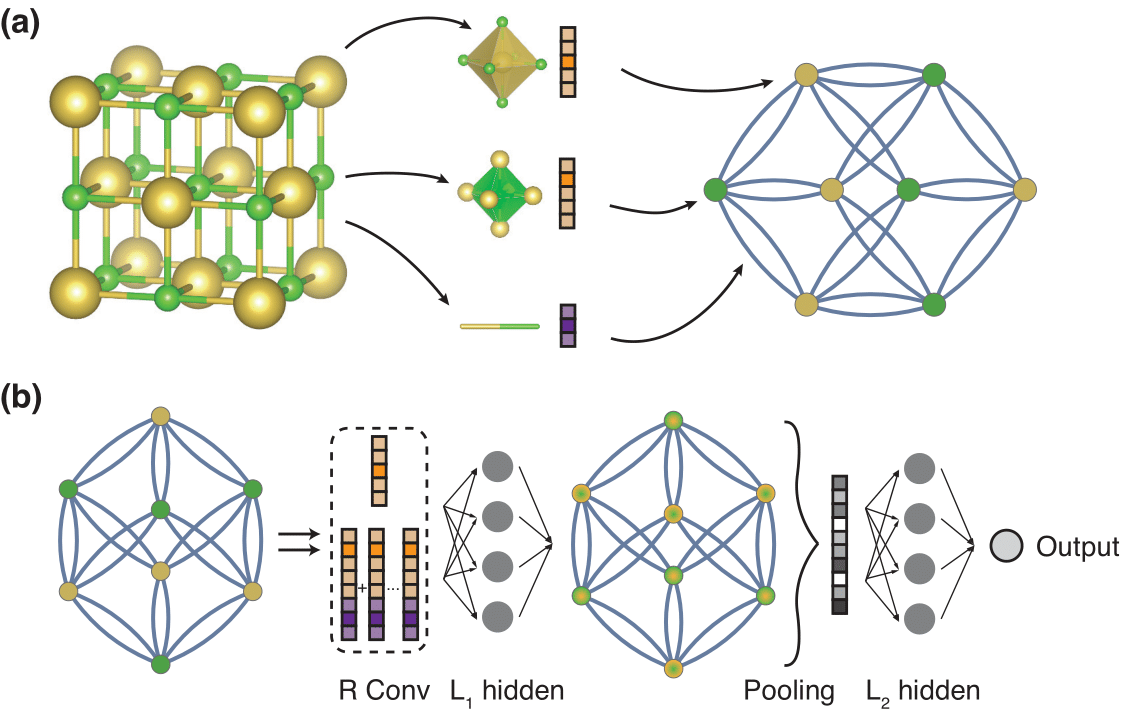

The most accurate algorithm is given by crystal graph convolutional neural networks (CGCNN), they take as input a graph that represents the topology of one cycle of the MOF as shown in Figure-2. Then they combine the local effects these links and nodes have with convolutional layers and by increasing these effect windows in a given cascade of convolutional layers we extract the properties we trained for. So the convolutions are utilized here to map the spatial aware local chemical effects to our model. This configuration may have problems with the generalization of new building units (as they have to be covered extensively in the training data) and vertical scalability (as the required computation power increases enormously if we want to train on larger MOF-configurations). Also it is necessary to obtain a 3D-representation of the stable MOF beforehand, in order to extract a topology, this is a practical challange which requires a lot of computation power for exploratory analysis of hundreds of thousands of material structures. This is a reason for Zhonglin et al. to propose a new architecture that aims to solve some of these issues.

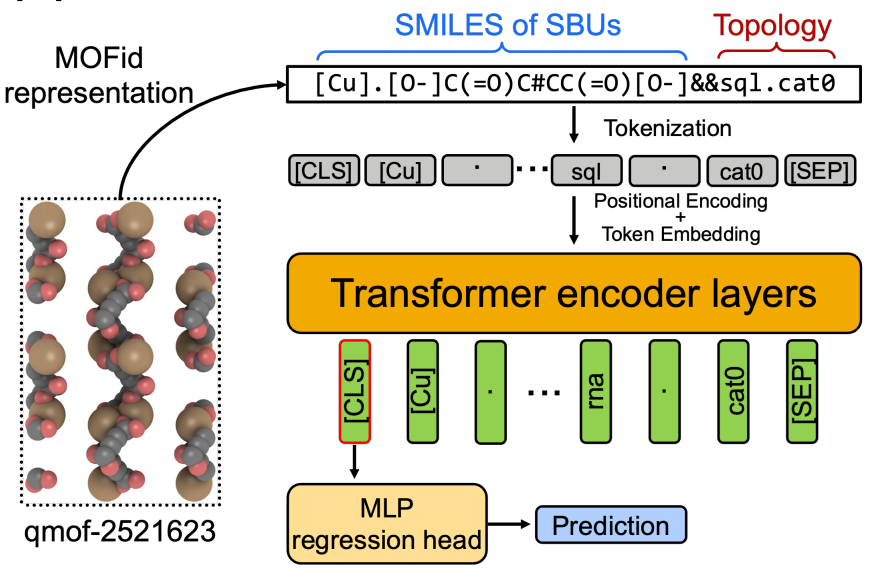

The Transformer architecture

Now finally we come to the new paper that we review. Zhonglin et al. are using transformers for material property prediction. To accomplish this, the authors employ the MOFID format, which offers string representations that can be easily tokenized, to predict material properties. These tokenzied strings provide an input instance, that includes information about the secondary building units (as arguably the most important data for material behaviour), as well as some hints on the topology of the network. These strings will be tokenized into single tokens and transformed into an embedded vector representing this token. After this attention maps are computed. Attention Maps can either refer to self-attention or to cross-attention, both are used in transformer models. Self-attention enables us to capture semantic relations within the instance and cross-attention enables us to relate those modeled semantics to other instances. By employing both types of attention, we establish connections between the internal structure of the input and potential output results. A attention head will compute the degree of relevance between an input or output token and itself or other tokens at the given position. Generally multiple attention heads are used and their output combined and normalized (in our case it will be 8 heads). The most simplified explanation of what a transformer does is: given a part of the input, at which other parts do you have to look to understand the semantics of this part in the overall instance?. Subsequently, these building blocks are followed by a shallow network that establishes a connection between these semantic relations and the desired material property, such as CO2 adsorption.

Transformers, in general, yield impressive results when certain criteria are met. Firstly, transformers necessitate a significantly larger training dataset compared to deep neural networks or traditional machine learning approaches. However, this poses challenges due to the scarcity of data available for MOFs and their properties. Furthermore, the data exhibits high heterogeneity, with numerous properties having limited values and inconsistent quality across various datasets. Secondly, we must address the challenge posed by the topology-agnostic input format, which has limited capabilities to accurately map the structure to specific properties. This provides us with an issue, as we need certain considerations about topology to achive the accuracy we desire, since as explained previously, only considering the building units opens up the representation to a lot of different invariances that come with different material properties.

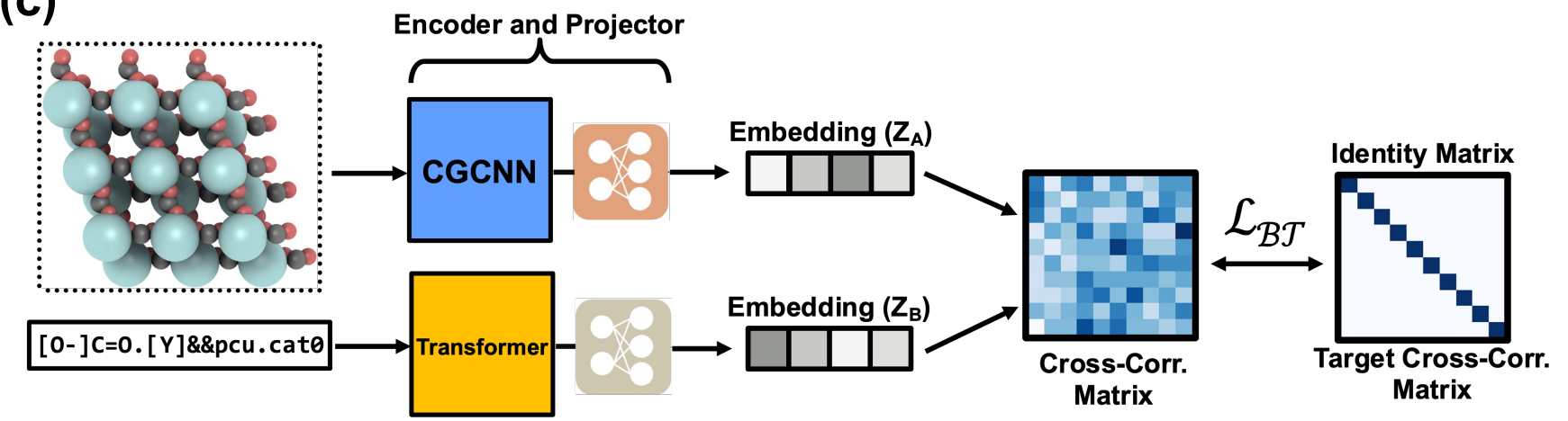

Traning of the Transformers

To address these challenges, the authors propose a solution involving self-supervised training using the well-established and accurate CGCNN model. We call this self-supervised learning method knowledge destillation, where a teacher network in our case the crystal graph convolutional neural network, teaches the student network, here the MOFormer, a representation of the model. In this approach, we leverage the available model to acquire a compressed representation of the input instance, offering several advantages. This has several advantages: We can learn the transformer model parameters more data efficient, as we now only need the MOFID and the Graph now to train a representation, rather than using different properties and resetting the deeper layers severeal times in the training process (as you would probably to in a multi task training). Furthermore, our objective is to learn a latent representation that encompasses topology considerations, leveraging the CGCNN representation where the complete topology is provided as input. Consequently, our goal is to enable the transformer to initially learn a representation that includes the absent topology information from the input data. Subsequently, this representation can be utilized to enhance the prediction of material properties.

So now that we have a satisfactory representation, we need to proceed with the original property prediction. Standard training algorithms are employed for the original property prediction. This includes the regression head, as seen in Figure 5, or some other head consisting of dense layers, to be trained for a specific parameter such as in the paper for instance CO2 adsorption (or Methan adsorption, H2 storage, pore size, electric charge in pores, …).

The authors utilize data from several material databases, including:

- The

Reticular Chemistry Structure Resourceoffers us 3D representations as well as Systre-Notations of possible Secondary Building Units (particularly nodes). This data can be utilized to automate data synthesis. Numerous resources provide organic structures that serve as ligands. - The

Cambridge Structural Databasecontains a lot of different Metal-Organic Compounds, that is also a lot of MOFs and organic linkers. - The qMOF-Dataset as in [7] employs high-throughput density functionality theory electron simulations to acquire material properties, including optimized geometries, absolute energies, band gap density of states, charge densities, and other attributes, thereby creating a substantial dataset of theoretical MOFs.

- The hMOF-Dataset [4] provides us with nearly 140 thousand hypothetical MOFs encompassing pore size, methane storage, and surface size. It was automatically generated from secondary building units with templating, in accordance with the customary practices in reticular chemistry.

- Lastly in [3] the Authors provide a collection of datasets named CoRe MOF (Computation-Ready, Experimental Metal–Organic Framework Database),a comprehensive compilation of datasets sourced from diverse databases. This resource undergoes extensive duplicate elimination and encompasses a wide range of attributes suitable for training.

All these datasets have been used to train the transformer once simply supervised and once with pretraining as outlined previously. The inclusion of self-supervised training substantially enhances accuracy, reinforcing our confidence in the authors’ conceptual approach.

Latent Representations

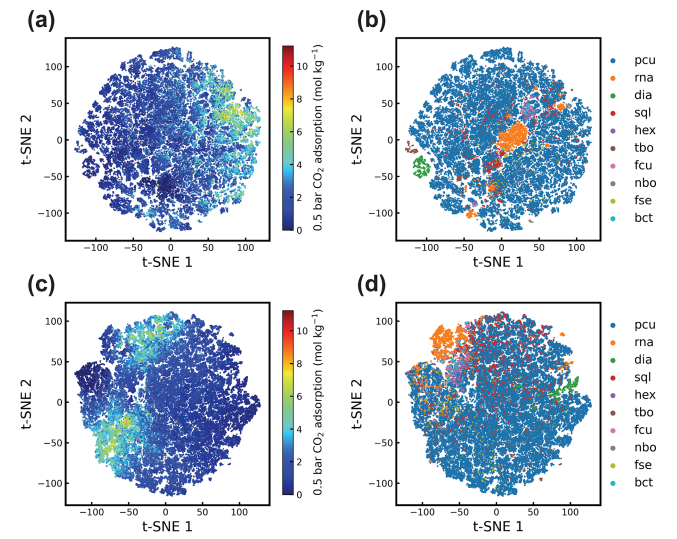

While undertaking representation learning with CGCNN and MOFormer, it is possible to visualize the clustering patterns of the most prevalent topologies, providing valuable insights into their impact on property prediction. We can see this illustrated in Figure 6, where Zhonglin et al. compare the clustering to topology type and C02 adsorption. They see that the transformer representation still assigns greater importance to the topology encoding, as the topology category is explicitly emphasized, in contrast to the results of the neural network. This is illustrated by some of the insular topology instances, that are only given in (b) but not in (d). Consequently, the transformer may exhibit limited performance with rare topologies. This is expecially bad for exploratory uses, as there we often encouter instance that are not well researched.

Figure 6: The clustering of the latent representations from [1].

In (a) and (b) we see the transformers representations, once colored in by the gas adsorption and once by the topology.

In (c) and (d) we see the same data for CGCNN representations respectively.

Head weight evaluation

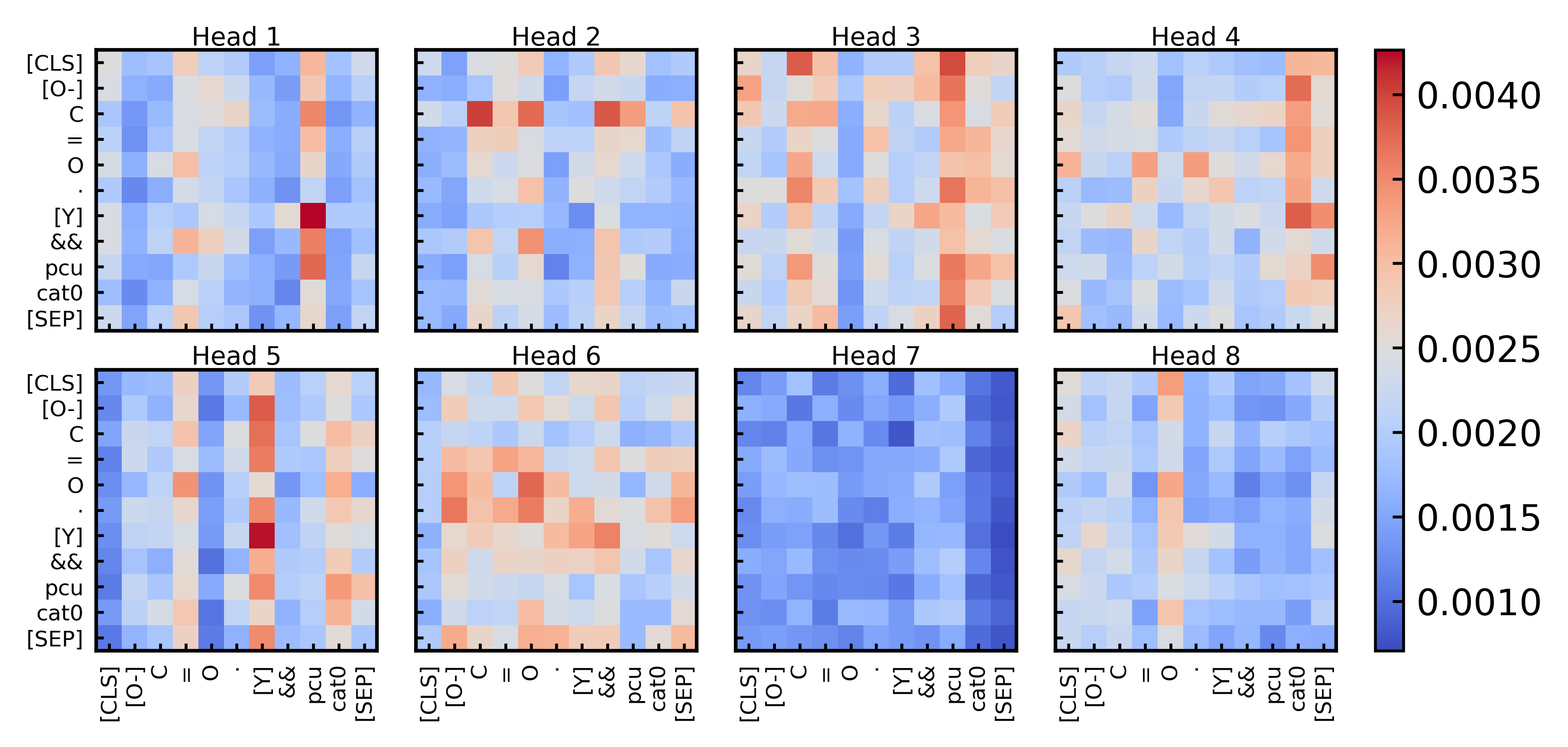

Additionally, the authors highlight that we can use the visualization of the attention weights to find out how the transformer learns to interpret an instance. This means we can extract how certain parts in the model attend to other parts and make it a bit more explainable what is important in an architecture. We can here use the model of chemical relations in the less deeper layers of the neural network, to gain insight in the actual chemical material. The authors for instance remark that the metal node ytterium and the pcu topology encoding attend very strongly in head 1, this means in order to unterstand the effects of the MOF we can especially look at these combinations of nodes and topologies. This is still area of future interdisciplinary research, but might be also useful for postsynthetic modifications.

Figure 7: Example of the learned multi-head attention, shows atttention between metal nodes and topologies

Evaluation

What the researchers took from it ?

- Data efficiency We can see that in very small instances the MOFormer model outperforms CGCNN, which makes it more valuable if the training data set is small. Although in larger training data sets CGCNN always outperforms transformer architectures.

- Accuracy evaluation While the accuracy MOFormers is signifcantly worse than the ones of Graph Neural Networks, we can see that the dual pretraining helps increase the accuray of both. It is still to see whether on large datasets (>1Mio) we will get more accurate results with transformers than CGCNNs

- MOFormer still provide a considerable vertical scale up, as now the prediction does not rely on atoms anymore, but tokens that represent structure properties and secondary building units that can be of different sizes. Also we have horizontal scale up, as now we are a lot more cost effective since we can now compute the property prediction more cheaply, which is necessary considering that the main usage of these models is high throughput computational screening and we expect the number of hypothetical instances to grow in future enormously.

- We provide a more lightweight representation of MOFs as input format (now we have MOF-ID instead of topology graphs), which enables researchers to come up with new MOFs, test them more cheaply and only investigating promising results later on.

References

[1] Zhonglin Cao, Rishikesh Magar, Yuyang Wang, and Amir Barati Farimani. “MOFormer: Self-Supervised Transformer Model for Metal–Organic Framework Property Prediction.” Journal of the American Chemical Society, 145(5):2958-2967, 2023. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.2c11420

[2] Benjamin J. Bucior, Andrew S. Rosen, Maciej Haranczyk, Zhenpeng Yao, Michael E. Ziebel, Omar K. Farha, Joseph T. Hupp, J. Ilja Siepmann, Alán Aspuru-Guzik, and Randall Q. Snurr. “Identification Schemes for Metal–Organic Frameworks To Enable Rapid Search and Cheminformatics Analysis.” Crystal Growth & Design, 19(11):6682-6697, 2019. DOI: 10.1021/acs.cgd.9b01050

[3] Yongchul G. Chung, Emmanuel Haldoupis, Benjamin J. Bucior, Maciej Haranczyk, Seulchan Lee, Hongda Zhang, Konstantinos D. Vogiatzis, Marija Milisavljevic, Sanliang Ling, Jeffrey S. Camp, Ben Slater, J. Ilja Siepmann, David S. Sholl, and Randall Q. Snurr. “Advances, Updates, and Analytics for the Computation-Ready, Experimental Metal–Organic Framework Database: CoRE MOF 2019.” Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 64(12):5985-5998, 2019. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jced.9b00835

[4] Christopher E. Wilmer, Michael Leaf, Chang Yeon Lee, Omar K. Farha, Brad G. Hauser, Joseph T. Hupp, and Randall Q. Snurr. “Large-scale screening of hypothetical metal–organic frameworks.” Nature chemistry, 4(2):83-89, 2012.

[5] Tian Xie and Jeffrey C. Grossman. “Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks for an Accurate and Interpretable Prediction of Material Properties.” Physical Review Letters, 120(14), 2018. DOI: 10.1103/physrevlett.120.145301

[6] VV Butova, MA Soldatov, AA Guda, KA Lomachenko, and C Lamberti. “Metal-organic frameworks: Structure, properties, methods of synthesis and characterization.” Russian Chemical Reviews, 85(3):280-307, 2016.

[7] Andrew S. Rosen, Shaelyn M. Iyer, Debmalya Ray, Zhenpeng Yao, Alan Aspuru-Guzik, Laura Gagliardi, Justin M. Notestein, and Randall Q. Snurr. “Machine learning the quantum-chemical properties of metal–organic frameworks for accelerated materials discovery.” Matter, 4(5):1578-1597, 2021.