Stochastic Search using MCMC in the Game of Life

Published:

In this article I will look at Conway’s Game of Life and introduce a new way to find interesting patterns, such as methuselahs, diehards or oscillators. Interestingly the specific goal is less interesting and the software can be extended easily in order to introduce a new goal.

My aproach: Instead of looking simply at random boards, I start with random initial boards and try to permute promising candidates sucessively, while relatively bad boards get substituted more frequently. In theory this helps leveraging the knowledge of candidates that are not great, but have given potential. In the next section I briefly explain the Game of Life and the goals of the algorithm.

Game of Life

The Game of Life is a simple cellular automaton, with esepecially easy rules and good emergent behaviour. The rules can be reviewed at Wikipedia. Often the Game of Life is considered a Zero-Player game, where the initial configuration is fully deterministic of the complete simmulation.

Mechanics and Modelling

The Game of Life is modeled as an infinite 2 dimensional raster of cells that are either alive or dead (0/1). Most cells, if not explicitly set, aredead at the start and can come alive if it has 2 or 3 live neighbors. If it has less then two neighbors it dies because of underpopulation, if it has more than 3 it dies because of overpopulation. Internally we can model a board as a 2 dimensional tensor and each update as a convolution with a specific 3x3 kernel that thresholds the number of neighbors in both directions. Using this modelling strategy we can effectively use the GPU (using torch) to parallelize board operations.

Common Approaches - apgsearch & Genetic Algorithms

One way to find interesting patterns is to search random generated patterns, these are called soups (thus this method is mostly refered to as soupsearch). One popular software to do this is apgsearch for each pattern the program records still lifes, oscillators, spaceships, periodic linear infinite growth patterns, “unusual growth” patterns, methuselahs and diehards. The problem with this approach is, that each run we generate new patterns and if there is nothing special we discard them, which includes the overwhelming part of all possible boards. We have a 100 % exploration weighting and do not leverage informations from the previous boards at all.

A second commonly used approach to the search is the use of genetic algorithms. With this we start search in a randomize distribution, but score each board with a fitness parameter and simulate natural evolution by “breeding” good boards and letting bad scoring boards “die”. This leverages especially local structures as the breeding mostly retains patches of boards, while other areas and properties are discarded. So we have not only exploration but also exploit our knowledge about the previous boards.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo

In my approach we use Markov Chain Monte Carlo Sampling as a stochastic search method to gradually improve good boards and substitute bad boards.

Interperetation of the taks

We define a bounding box for the initial configuration and consider each cell in this bounding box as editable. So for instance in our environment of a 16 x 16 box, we have a 256 dimensional discrete environement. Within this environment we begin constructing markov chains, this means we slightly permute the board by proposing an alteration and select good candidates. This can be seen as sampling from a probability distribution that maps from the initial configuration to a specific property of the board. In general this is not a “probabilistic” function, but due to the large search space of 2 to the power of 256 and the missing algorithms to efficently determine general properties of each board due to the turing completeness property of Conways Game, we consider the distribution intractable and approximate it using statistical modelling.

Please be aware, that each board configuration in itself is also a perfect markov chain as each step is completely and only determined by the step beforehand, but this is not the chain meant in this context.

Functionality of MCMC

We construct a markov chain by firstly introducing a random board (In general the algorithm works batched with several boards but I focus on the one chain setting for simplification). Then we score the first board and compare the score of the board to a second board that is permuted based on a randomized proposal and accept it using the Metropolis-Hastings acceptance rule. In a short formulation: we accept a proposal with a random probability that is higher, proportionally when the score is higher and less when the score is lower.

Samplers and Chains

In my code we abstract each Chain in a class, that deals with applying the Metropolis-Hastings Acceptance Rule. Additionally every chain manages a temperature, that is used to compute the acceptance at first very liberal and get more conservative over time. This is used to further advance the exploitation vs. exploration dilemma, where we first search very open for new global maxima and get more local in the refinement later on. There are several schedulers for different temperature behaviours to try out:

- ExponentialScheduler - Make a cooldown based on an negative exponential score, large exploration early and very low exploration at the end

- PlateauExponentialScheduler - Start with a plateau at the first steps and after plateau reduce exponentially

- OscillatingScheduler - Add an oscillating component to the exponential scheduler

- AdaptiveScheduler - Add an adaptive reheating component to the oscillationg scheduler

The chains are managed in a sampler that contains each step and can be used to flexibly add functionalities via different hooks.

Proposals

Proposals are one of the essential steps to recieve good results. The grade to which the board is permuted is determined by the proposal that is applied. Typically we do not have just one simple proposal but consider a lot of different proposals and combine them with given probability distribution.

We have low entropy proposals sich as:

- Single Flip - Flip the value of a single bit

- Block Filp - Flip the value of a specific block (2x2-Block by default, can be extended to other sizes)

We also contain some high entropy proposals:

- Area Transform - Change an area by flipping or rotating it

- Pattern Insert - Insert a known pattern from a fixed (small) size, such as a glider …

- Patch Neural Network - Insert a pattern (typically 3x3) based on the surounding environment from a neural network that is trained with interesting patterns that already exist

- New Board - Introduce a completely new random board

Scoring

The second essential component for a good MCMC-Search is the scoring mechanism. A good scorer should define the properties of the board we have in the end. Besides this we also have to define a smooth scoring function that increases over time building to a board that is more likely to result in a board with our desired properties. So just hoping for a good board to emerge in a greedy setting is okay, but it works better additionally using a smooth heuristic. So again a combined approach of several scorers seems good.

Implemented Scorers include AliveCellCountScorer (Counting alive cells after the simulation stabilitized), StabilityScorer (Reward stability over the simulation), ChangeRateScorer (Rewards Change Rate after a given number of simulated steps), EntropyScorer (Scores entropy of the board), ChaosScorer (Scores chaoticity based on growth, uniqueness and entropy), DiversityScorer (Rewards a good balance between alive and dead cells), OscillationScorer (Detects and scores oscillations based on temporal length) and MethuselahScorer (Awards scores to patterns that stabilize last and contains a lot of alive cells at the end).

Typically Scores have to be between 100 - 200 at the start to scale right with the temperature. Otherwise the temperature has to be adapted.

Improving the Search

Since MCMC is still very computationally intensive, especially when simulating a lot of steps of Conways Game, I tried to improve the efficiency of the algorithm via several methods. The first way is to look at different Proposals, Scores and Schedulers and adapt each one. Unfortunately this is based on the Scorer and the goal you hope to accomplish. Also I added hooks in the scorer to efficiently add mechanisms such as doing reheating based on acceptance rating or adapting the steps based on the result. Furthermore I included parallel tempering (also known as replica exchange sampling), this method swaps boards on different chains in order to re-energize stale chains.

Example Methuselahs: Developing Soups towards specific properties in the Game of Life using MCMC

Below you can see a simple script to that genereates 4 Independent Chains with each containing a batch size of 16, so in total 64 boards. The markov Chain has a step size of 2500 and 16 x 16 pixels to be set initially (to keep comparability to the classical soupsearch). In the following I provide some samples of patterns as well as training curves for different runs and configurations.

def main ():

device = "cuda"

engine = GoLEngine(device=device)

steps = 2500

box_size = (16,16)

# Init boards

boards = Board.from_shape(N=16, H=400, W=400, device=device, fill_prob=0.35, fill_shape=box_size)

# Scorer

scorer_steps = 55000

scorer = CombinedScorer(engine,

[(ChaosScorer(engine, steps=scorer_steps), 1),

(MethuselahScorer(engine, steps=scorer_steps), 1),

(ChangeRateScorer(engine, scorer_steps), 1)]

)

#Scheduler

scheduler = ExponentialScheduler(start_temp=1.0, end_temp=0.2, steps=steps)

# Chains with different proposals

def make_chain(proposal):

return Chain(boards.clone(), scorer, proposal, scheduler=scheduler, adaptive_steps=True, max_steps=20000)

chains = [

make_chain(CombinedProposal([

(SingleFlipProposal(use_activity_boundary=False, box_size=box_size), 80),

(BlockFlipProposal(box_size=box_size), 20),

(AreaTransformProposal(box_size=box_size), 10),

(NewBoardProposal(box_size=box_size), 10)])),

make_chain(CombinedProposal([

(SingleFlipProposal(use_activity_boundary=False, box_size=box_size), 60),

(BlockFlipProposal(box_size=box_size), 20),

(AreaTransformProposal(box_size=box_size), 10),

(NewBoardProposal(box_size=box_size), 10)])),

make_chain(CombinedProposal([

(SingleFlipProposal(use_activity_boundary=False, box_size=box_size), 40),

(BlockFlipProposal(box_size=box_size), 30),

(AreaTransformProposal(box_size=box_size), 10),

(NewBoardProposal(box_size=box_size), 30)])),

make_chain(CombinedProposal([

(SingleFlipProposal(use_activity_boundary=False, box_size=box_size), 60),

(BlockFlipProposal(box_size=box_size), 20),

(AreaTransformProposal(box_size=box_size), 10),

(NewBoardProposal(box_size=box_size), 10)]))

]

# Sampler

log_folder = os.path.join(f'results', f'logs', datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d_%H-%M-%S"))

# Hooks for peridoically dumping Boards & Reheating stale chains:

saver_hook = make_rle_saver(

outdir=os.path.join(log_folder, r"chain_samples"),

step_interval=100, # save every 50 steps

time_interval=60*15

)

reheat_hook = make_reheating_hook(min_accept_rate=0.05, min_score_delta=1.0, boost_factor=5)

sampler = Sampler(chains, log_dir=log_folder, post_step_hooks=[saver_hook, reheat_hook])

results, history = sampler.run(steps=steps, log_interval=1)

plot_history(history, show_chains=True)

In the example above, we initialize multiple chains of boards, each exploring the search space differently based on the proposals and schedulers assigned. The use of low- and high-entropy proposals ensures both local refinements and global exploration, while the Metropolis-Hastings acceptance rule allows the system to probabilistically favor boards with better scores. Scorers play a crucial role in guiding the search. By combining metrics like chaos, methuselah longevity, and change rate, we define a smooth heuristic that nudges the chains toward configurations likely to produce interesting emergent behavior. Over time, the temperature schedule shifts the search from broad exploration to local exploitation.

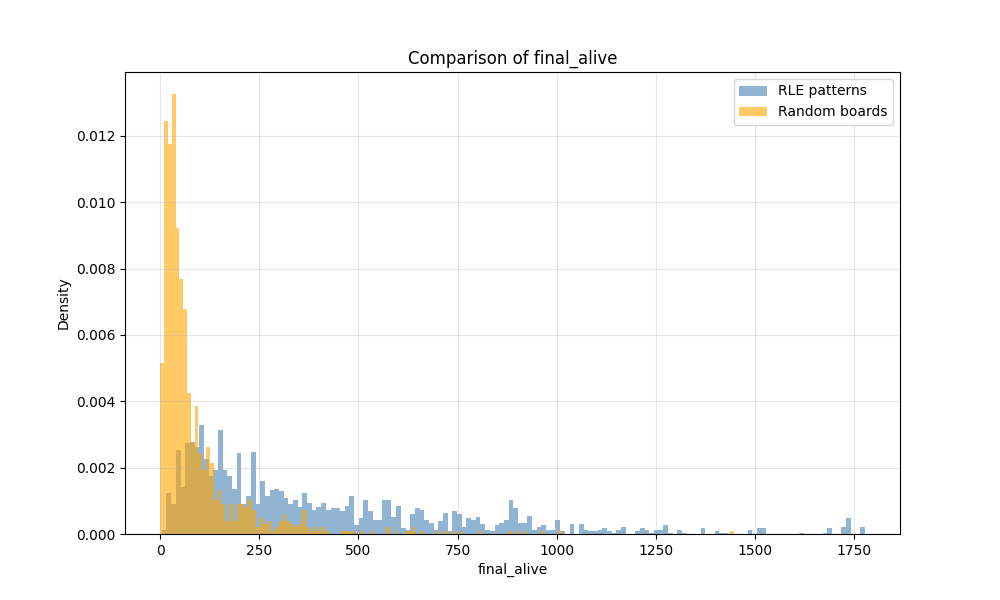

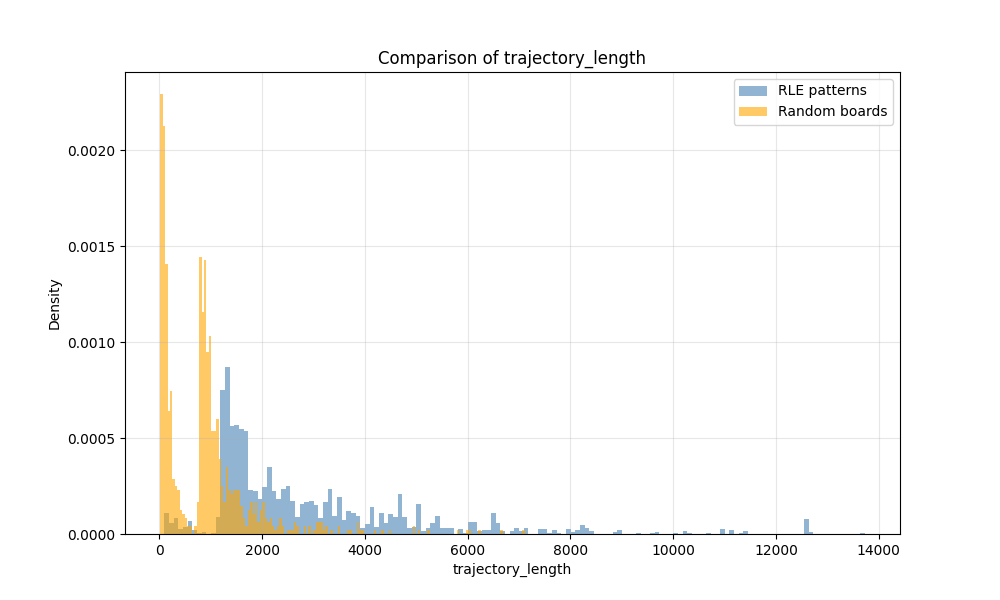

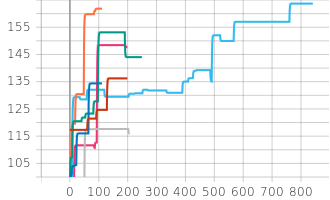

Visualizing results demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach. Comparisons against random initial boards show that MCMC-driven searches yield more alive cells, longer-lived structures, and higher-quality emergent patterns. Stepwise scoring plots illustrate gradual improvement over time, validating the combined effect of proposals, scorers, and schedulers.

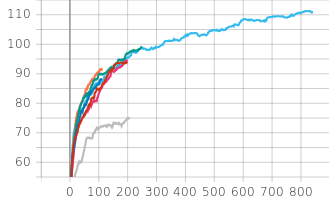

Also we can see the improvements over time if we plot each chain, notably this is only the combined score not the length to stabilizing:

Stepwise evolution of the combined score for different MCMC chains over time. The legend shows the chain configurations: Standard 2500 Steps (orange), Low-Entropy 500 (dark blue), Low-Entropy 200 (red), Standard 2500_2 (bright blue), Standard 200 (pink), Plateau 250 (green), Oscillating 250 (grey). Note that these scores reflect the combined scoring function, not the time to stabilization.

Results

Ultimately, this stochastic MCMC framework allows us to generate and refine Game of Life boards toward specific objectives without hardcoding patterns. By tuning the scoring functions, proposal distributions, and temperature schedules, the method can be adapted to search for a wide variety of phenomena, from methuselahs to oscillators and beyond. The result is a flexible, probabilistic search engine for the Game of Life that learns from past boards, leverages promising candidates, and systematically explores the vast combinatorial space of possible initial configurations. With this we can search patterns sampling from already existing patterns that are more likely to produce good results. So the chain should start with boards that have random length and sample from progressively longer boards. We can visualize this in comparison against samples from a random distribution:

Some long patterns found using the chains above include: